Women

in mining

Text and interviews Eleonora Vio

Photos and videos Ines Della Valle

Wars, blood minerals, diseases and sexual violence. For the majority of public opinion, this is what the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) is all about. But, today, in the eastern provinces of the Central African country, which is as large as the whole of Western Europe, we are witnessing some unexpected changes. In the midst of one of the richest areas in the world for subterranean resources, but where the GDP per capita is one of the lowest, women – despised and discriminated against for centuries – are leading a revolution that is helping not only to change the image of this country, but also that of the artisanal mining sector (AMS). So far, the latter has only been known for its outpouring of corruption and the many atrocities, hidden away and later forgotten, that have been committed under its name. However, since 2006, women have started to unite in associations and ten years later have gotten together around a tightly-knit network known by the French acronym of RENAFEM (National Network of Women in Mining). Within this net are some ambitious, sometimes privileged, women who, thanks to the mineral business, have reached economic and social standards that pair those of their male counterparts (e.g. Angelique Nyirasafari, Yvette Mwanza and Emilienne Intongwa). Others who started from a more disadvantaged position have gradually caught up and today don’t withdraw before men’s attempts to discriminate them (women such as Murekatete Beatrice or Mwamini Makanyaka). Finally, there are those who understood the relevance and centrality of the women miners’ struggle and, despite their initial distance from this world, left everything behind to embrace the cause (such as Viviane Sebahire or Veronique Miyengo). Focusing on the opportunities the AMS can offer to women doesn’t mean forgetting that they are still too often vulnerable victims of a system based upon male hegemony (e.g. mama twangaises). But, rather, than due to economic, political and social circumstances, women feel the need to demand their own rights and, by escaping the dominating framework of total subjugation towards men, change a secular and malfunctioning balance. The journey Congolese women must undertake to fully emancipate within the AMS is long, and doesn’t end here. RENAFEM has proven to be a powerful network, helping thousands of women self-determinate and liberate themselves from stereotypes and misconceptions. In order for their social growth to rise at the same pace as economic growth – as well as to see a tangible improvement in the life of all women miners – it is the institutions that must intervene.

“Congo is a jungle, where impunity, bad administration and injustice are very widespread,” claims Angelique Nyirasafari, one of the women leaders. “Justice is part of the transaction and those who don’t have money don’t get to be listened to.” As long as the highest levels of this system don’t change, it will be women who once again are paying the highest price.

1

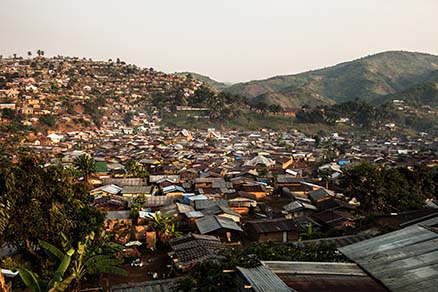

1 / In Goma there are only two paved roads. The rest is volcanic terrain.

2 / Most of the houses in the capital lack both water and electricity.

3 / One of the most common transports people use to move across the town is mototaxis.

4 / Most of the Congolese population lives in make-shift shacks.

2

3

4

Angelique

Nyirasafari

In Goma there are two paved roads. One leads to the international airport, the other runs along the coast, where the expats’ fancy compounds are located. All the rest, including Angelique Nyirasafari’s place, are only reachable by travelling on uneven tracks, constantly interrupted by massive, threatening rocks. In Nyirasafari’s case, as you pass a tiny metal door, which is the only thing that can be glimpsed from the outside, the dark volcanic soil typical of the city gives way to a grand villa, immersed within the exotic vegetation. Nyirasafari is a distinguished mineral trader and a member of COOPERAMMA. In 2011, it was the first mining cooperative to be established in North Kivu, in Masisi territory that is rich in cassiterite (tin) and coltan (tantalum).

There are three kinds of traders. Those who work with the diggers, which means that they pay the diggers to do the work and then sell the minerals to the big companies or, else, to the transforming firms. There is a second category of traders, which consists in those who buy (minerals) directly in the mining pits. They go to those places, they purchase (minerals), and then they sell them. Finally, there is a third category of those who own a pit, work there, and once they find the minerals, they sell them to the big companies or to the transforming firms. A businessperson usually fits within either the second or the third category, but I fit all three.

There are three kinds of traders. Those who work with the diggers, which means that they pay the diggers to do the work and then sell the minerals to the big companies or, else, to the transforming firms. There is a second category of traders, which consists in those who buy (minerals) directly in the mining pits. They go to those places, they purchase (minerals), and then they sell them. Finally, there is a third category of those who own a pit, work there, and once they find the minerals, they sell them to the big companies or to the transforming firms. A businessperson usually fits within either the second or the third category, but I fit all three.

Nyirasafari is the second of eight children that her mother, the second of her father’s three wives, had. Her father was a big farmer. “My father had the means to send us all to school but, because of our culture, my sisters didn’t care about anything other than having kids and getting married,” she says. “I was the exception. I didn’t want to get married before finishing my studies and my father supported me.” Despite her privileges, Nyirasafari, like most Congolese people, endured some very hard times. During the first Congolese war, which erupted in 1996 as a direct consequence of the genocide that occurred in Rwanda two years earlier, Nyirasafari – who belonged to the well-off Hutu community based in the DRC – lost both her brother and his wife. In fact, during the ravenous hunt the Tutsi organised to eliminate their Hutu oppressors who had found shelter in Congo from Rwanda, those who only shared an ethnic lineage with the Hutu paid a hefty price. “Even if they told us that those who got kidnapped were later murdered, we can’t be 100% sure,” says Nyirasafari. “We never saw their bodies.” Since her brother disappeared, his children have been living with her.

focus

Looking

backwards

read

focus

The mining

cooperatives

Germaine

Bumbu

read

Until 2015, Nyirasafari was involved in the humanitarian sector but, as she craved spending more time at home with her kids, she decided to quit. With the money she put aside, she started, first, buying minerals from small traders and selling them in Goma and later dealing directly with the miners in the mining sites. Although the mineral business is dominated by men in the DRC, it is still the fastest way women have to climb up the economic and social ladder. While Nyirasafari’s interest in this field is quite recent, women actually started entering the (mainly artisanal) mining sector in 1982, pouring into it in greater numbers in 1996 when the national mining company, SOMINKI, was shut down at the beginning of the war and thousands of men employed there became jobless. On entering the mining sector, Nyirasafari decided she would improve the working standards of her colleagues alongside her career. The turning point was the National Conference of Women in the Mining Sector held in Bukavo, the capital of South Kivu, in 2015, supported by the World Bank and the Congolese government. There, they set the foundations for what, two years later, became the National Network of Women in Mining (or RENAFEM). After attending that conference, Nyirasafari decided to form an association named Dynamics for Women in the Mining Sector (FEDEM), which flanked COOPERAMMA in the protection of women in Masisi territory. “In Congo being a woman is the greatest challenge,” Nyirasafari says. “Often it’s women themselves who feel inferior to the men and men feel legitimised to behave, as if they were really superior.” For this reason, joining an association for many women becomes the only way out from the constant pressure the society exerts upon them.

“In 2016 we got invited at an international conference focused on women in mining in Bukavo. After attending it, we realised that it was about time to get involved and protect women in this field. That’s how we created FEDEM. What I learnt is that, as women who work in the same mining sector, we must support each other, because if we don’t, women who are still exposed to abuses won’t ever get their voice heard. If we are closed, communication gets easier and more effective.”

“In 2016 we got invited at an international conference focused on women in mining in Bukavo. After attending it, we realised that it was about time to get involved and protect women in this field. That’s how we created FEDEM. What I learnt is that, as women who work in the same mining sector, we must support each other, because if we don’t, women who are still exposed to abuses won’t ever get their voice heard. If we are closed, communication gets easier and more effective.”

Today, Nyirasafari is also involved in DRC politics and will soon be running as a national deputy for the Senate, to give voice to the trampled on rights of the women of Masisi. “Inside COOPERAMMA I am the only woman with a diploma,” she says somewhat disappointedly. “Women from my area only think about getting married and, if things keep going this way, soon there will be no more literate women in Masisi.” Since local miners feel frustrated about the privileges granted to outsiders such as Senator Mwangachuchu, they all too often join armed groups to make up for their subdued sense of injustice. By doing so, they leave an often too heavy burden upon the women.

focus

RENAFEM

read

1

1 / Angelique Nyirasafari is a well-known trader of North Kivu and her phone rings all-round the clock.

2 / With her family, Nyirasafari lives in a beautiful and fully furnished house.

3 / Kasomba or transporteuses women carry up to 25kg stones on their backs 2-3 times a day.

2

3

Yvette Mwanza

Yvette Mwanza insists that we meet neither at her place, nor in the firm that she runs specialising in the transformation and sale of minerals, when she’s not too busy dealing with her more important official tasks. Instead, we drive beyond the chaotic city centre of Goma, until we reach a quiet and charming lodge a few kilometers away from the Rwandan border. As we walk down the terraces that gradually lead to the shores of the Kivu Lake, we glimpse a well-built woman, wearing a green silky dress that matches a set of shiny jewels that catch our attention. Yvette Mwanza is the Vice-President of the Mining Operators in the Chamber of Commerce of the DRC, as well as the President of its North Kivu branch. She is also a role model for most Congolese women and, certainly, for those women involved in the mining sector.

“In the Committee I am the only one (woman) for the North Kivu province. If we compare (North Kivu) with the other provinces... the president of South Kivu is a man, of Maniema is a man...I think, maybe, I am the only woman who has this position, as the President of the Committee of the Mining Operators in one province, in the mining sector. I am maybe the only one.”

“In the Committee I am the only one (woman) for the North Kivu province. If we compare (North Kivu) with the other provinces... the president of South Kivu is a man, of Maniema is a man...I think, maybe, I am the only woman who has this position, as the President of the Committee of the Mining Operators in one province, in the mining sector. I am maybe the only one.”

The mission of both the Chamber of Commerce and Mwanza is to identify risks within the mining sector, in order to regulate the sale and export of minerals from post-conflict areas that, like North Kivu, are still strongly unstable and characterised by a high presence of armed militia. “Despite the obstacles, I make sure that the supply chain of the minerals destined to go to foreign trade is responsible and that, at least for the 3Ts, the international standards of traceability are implemented,” Mwanza explains, referring to the basic minerals the growing electronics industry relies upon, such as tin (cassiterite), tantalum (coltan) and tungsten (wolframite). “Since both gold and precious stones slip away from the regulations imposed by the official market, and are often exposed to trafficking and smuggling, I am also backing the authorities in the creation of a Stock Exchange.” Mwanza has a very clear vision of the direction the mining sector must take in order for the resource-rich North Kivu to become competitive on a global scale. “The first thing that needs to be done to increase the still insufficient level of production,” she explains, “is pushing miners to form cooperatives, which in turn need to receive material support from the State to get mechanised and be able to exploit larger areas in a shorter time. This way they can make bigger profits.” Things should be the same for women, even if they often cover marginal roles otherwise performed by the machines. “It’s not true that illiterate women risk losing their job, if mining gets mechanised,” claims Mwanza.

focus

Traceability

read

“They (Women) must be formalized and have a cooperative with all due documents. Also, they need to get capacity building in terms of management. In order to get some financement from either a bank or some other institution, they must show that they have good management. Now we have an advantage with the new mining code, because it gives the cooperatives of miners both the possibility and the opportunity to get a mining title and a permit for exportation.”

“They (Women) must be formalized and have a cooperative with all due documents. Also, they need to get capacity building in terms of management. In order to get some financement from either a bank or some other institution, they must show that they have good management. Now we have an advantage with the new mining code, because it gives the cooperatives of miners both the possibility and the opportunity to get a mining title and a permit for exportation.”

focus

The gemstones

stock exchange

read

The women’s issue has become pivotal since the RENAFEM network was formalised in 2015. “I attended both conferences in Bukavo and Lubumbashi,” Mwanza says. “For a while the World Bank had been trying to present my case as an example of a success story, to encourage the other women to believe in themselves and never renounce to the idea of growing within the mining sector.” Mwanza is the first to admit that she is not like any other woman, though. “Probably, if I had stayed in the village in Kasai where my father was born, I wouldn’t be like this,” she says. “The environment I was raised in helped me become the woman I am today.”

Mwanza is the first of eleven children her mother had from a well-renowned judge of the Supreme Court. The Congolese legislation dictates that people pursuing this career must change place every couple of years, to avoid conflicts of interests, which is why Mwanza’s first memories are blurred. Given the high social status of her parents, though, no one in her family had to give up their career to build up a family, or vice versa. “According to our local mentality, being a woman is a misfortune. But my parents were different,” she says frankly.

“We women must be involved and be part of the solution. We can’t always be the victims but we must look forward and try to find solutions to the problems of gender, as well as of governance and security. We must be part of the solution.”

“We women must be involved and be part of the solution. We can’t always be the victims but we must look forward and try to find solutions to the problems of gender, as well as of governance and security. We must be part of the solution.”

Like the other women, Mwanza suffered the advent of the war in her own way, too. “I feared for our lives but I was also very concerned that, if I stayed in Congo, I would have to make compromises,” she says. “So many people offered me bright careers, but I didn’t want to work for the rebels controlled by foreign powers.” Mwanza left Bukavo – where she lived at the time – with her husband and found shelter in Rwanda, where she spent ten years until 2006, when she returned to Congo to vote at the first free multi-party elections in 46 years. She moved to Congo for good in 2007 when she was offered the management of the firm she still runs. As soon as her managing skills were ascertained, she was asked to cover more challenging roles, too. Today Mwanza wants to beat another record and become the first woman in North Kivu to hold a licence not only to export, but also to cut and sell finished jewels, designed by herself.

focus

The mining

code

read

1

2

3

1 / View of the southern part of Kamituga mining site dedicated to the gold artisanal extraction.

2 / Mama bizalu collect the stones discarded by men. These stones get later washed and crushed.

3 / In the northern mechanised part of Kamituga, after the concassage machine has ground the quartz stones, women wash and sieve the powder.

4 / Walungu mining site. Hands of women at work, as they crush the stones searching for cassiterite.

5 / Yvette Mwanza heads a firm specialised in the transformation and sale of minerals abroad.

6 / In Numbi mining site a woman washes the stones that will be lately crushed to get coltan.

4

5

6

Viviane Sebahire

Sometimes a person’s destiny is written from their very first day. This is surely the case for Viviane Sebahire, a doctor specialising in sexually transmitted diseases and reproductive issues. She is also the coordinator of the SOFEDI (Women’s Solidarity for the Integral Development) association, focused on the crucial battle to protect women miners’ rights in Walungu. At the final exams of her primary school, Sebahire already stood out from her school mates. Her dissertation titled The prevalence of the HIV virus between 1990 and 1994 was so articulate that it drew the attention of a doctor from Kinshasa who was visiting Bukavo in search of material to launch a program against AIDS across South Kivu. With a paper handwritten by a young girl, who had been able to sum up a very complex issue in a witty and straightforward way, the doctor flew to Belgium where he got the funds to kick start his research. At 15-years-old, Sebahire entered the first research team specialising in reproductive issues in South Kivu. In the meantime, she continued studying, got married and had kids. “I already had a boy and a girl when my mother, who was very progressive not only for that time but also for today, pushed me to go back to attend the university, saying that she would look after my children,” Sebahire explains. “She was the one who insisted that I took the contraceptive pill, to dedicate the following four years only to my studies and my career. I owe everything to her.”

Gender based violence and systemic rapes started in the 1990s, spiked during the second Great War (which formally ended in 2003) and became routine between 2006 and 2007. “Back then, I used to work at Doctors Without Borders and I called for the authorities to become grantors of the antiretroviral therapy programs aimed to slow down the spread of the virus,” Sebahire says, still visibly shaken. “Also joining that program was the Rwandan commander who led the revolt, himself HIV-positive. But I couldn’t know that his involvement was a farce.” One night, in fact, the commander sent some of his men to kidnap Sebahire with the probable intent being to abuse her. But her husband managed to hide her and organise an escape. “Having seen so many women broken by the war, and knowing that I could have been one of them, contributed towards making me more committed to what I do,” Sebahire claims. “But my interest in this field precedes all this.” Since 2006, Sebahire has also started helping women miners by handing out contraceptives to limit the spread of sexual infections and diseases in the mining pits. It was when she first set foot in the sites that she became aware of the physical abuses women are constantly subjected to and decided to create a program to promote their rights.

focus

Women miners:

the main challenges

Veronique

Miyengo

read

“We found out that women were prevented from entering the mining sites, because they didn’t have visit cards. Visit cards, in this case, means that women should have been regularly tested to make sure they didn’t have sexually transmitted diseases or HIV/AIDS. Instead of proceeding this way, someone started to sell non-authorised cards (at the black market), where it was only written: name, sex, HIV-positive or negative. We noticed that this procedure would discriminate women, because they were the only ones required to show, and buy, the card, whilst men were not asked to.”

“We found out that women were prevented from entering the mining sites, because they didn’t have visit cards. Visit cards, in this case, means that women should have been regularly tested to make sure they didn’t have sexually transmitted diseases or HIV/AIDS. Instead of proceeding this way, someone started to sell non-authorised cards (at the black market), where it was only written: name, sex, HIV-positive or negative. We noticed that this procedure would discriminate women, because they were the only ones required to show, and buy, the card, whilst men were not asked to.”

As Sebahire managed to uproot this and other wrongful practices, new ones would spring up to replace them. For instance, at some point the site managers prevented women from accessing the mining pits unless they paid 15,000 francs (roughly £8). Traders, pickers, washers… everyone was subjected to the same treatment. The only ones who didn’t have to worry about sharing their profits with anyone were, as usual, men. “Women miners earn up to £2.70 a day, if it’s a good day, and you ask them to pay an entrance fee?” asks Sebahire, opening her eyes wide. “This is pure discrimination. We divided women into groups and, amongst them, we chose and trained a representative. After this, with the help of a legal councillor we gathered the local chiefs, the police and the site managers, we proved, laws in hand, that the tax was wrong and had to be blocked. We still do this every three months.” The conditions of women miners in the area have steadily improved and, if men don’t stop trying to step upon their rights, women have developed better awareness and have become more resilient to their provocations. Sebahire’s choice to focus on Walungu as the first area of intervention was random. “We were contacted by the site managers because they feared the HIV contagion,” explains Sebahire. “When we arrived, we noticed other problems too.”

The lives of women miners are hard and at each and every level men subject them to different forms of discrimination. An example of this concerns women who are forced to negotiate their access to the mining sites through sexual activity. Sebahire believes – and she’s not the only one – that: “If they must be protected from a medical point of view, they are but not to be considered more socially vulnerable than other women.”

focus

Transactional

sex

Fideline

Mubukyo

read

“Sex is a mining activity like any other. We have two people based there (in Walungu), who hold awareness and communication sessions to promote behavioral changes. In those occasions, we distribute free condoms and we set up a private space for all those who want to get tested for HIV. We consider this as some kind of prevention measure. If someone enters this box and finds out that he/ she is HIV-negative, he/ she will take better care of his/ her health and will always use condoms, which - by the way - are distributed freely.”

“Sex is a mining activity like any other. We have two people based there (in Walungu), who hold awareness and communication sessions to promote behavioral changes. In those occasions, we distribute free condoms and we set up a private space for all those who want to get tested for HIV. We consider this as some kind of prevention measure. If someone enters this box and finds out that he/ she is HIV-negative, he/ she will take better care of his/ her health and will always use condoms, which - by the way - are distributed freely.”

1

2

3

1 / Viviane Sebahire works with her colleagues in the office of SOFEDI association in Bukavo.

2 / Walungu mining site. Some women wash the stones in the river, whilst others crush them to extract precious minerals.

3 / Walungu. At the end of the working day, women rest and chat along the river.

4 / Walungu. Lavaseuses women check the quality of the stones they are washing.

4

Emilienne Intongwa

The rainy season should be long over but heavy showers keep damaging the already non-existent road infrastructure. Every time the 4x4 vehicle stops shaking and lets itself go onto the muddy quicksand that covers the overhanging track, our muscles hurt. If the tragic end that befell the rusty frames abandoned on the road edges is miraculously escaped, a 180km journey that would normally take few hours will last up to an entire day. Kamituga is the third largest city in South Kivu but contains no more than a handful of mountain tracks. Hundreds of shacks are squeezed along the main road, selling fried snacks alongside the basic working tools for the backbone of the regional economy – the extraction, treatment and sale of gold.

focus

Kamituga

read

All of a sudden, in the middle of a junction, where old Jeeps challenge motorbikes and pedestrians to see who will reach the nearby mining site first, two old ladies in traditional dresses appear. They both point at the wooden ALEFEM (Association against the Exploitation of Women and Children in the Mining Sector) sign standing on the opposite side of the road, and wave to follow them. ALEFEM was founded by Francoise Bulambo and Emilienne Intongwa in 2006, a few years after the end of the second Congolese war, which hit Kamituga with particular intensity.

Like a phoenix that obtains new life by rising from its own ashes, Intongwa has re-elaborated her own tragic past and carved out a leading role for herself. “As we were seeking shelter far from the city, the Mai Mai armed militia kidnapped my husband. Since that day I haven’t heard from him. I kept running but they robbed me of everything,” she tells. “When I returned to Kamituga, I had nothing with me and, since, until that moment, I had worked in the field that had passed under the control of the militias, known to kill and rape each and every woman attempting to get her property back, I decided to move to another sector.”

focus

ALEFEM

Francoise

Bulambo

read

“I chose that job because, if I had wanted to do something different, I couldn’t have. Back then, there was nothing but mining. Moreover, the only society that was providing people with jobs was SOMINKI, which was destroyed by bombing during the war. Another thing is that my husband was kidnapped by a militia and I stayed behind with 7 children. I had to find a way to survive and give them food. The only answer was AMS.”

“I chose that job because, if I had wanted to do something different, I couldn’t have. Back then, there was nothing but mining. Moreover, the only society that was providing people with jobs was SOMINKI, which was destroyed by bombing during the war. Another thing is that my husband was kidnapped by a militia and I stayed behind with 7 children. I had to find a way to survive and give them food. The only answer was AMS.”

Intongwa obtained a loan from a trader to explore her own mining pit but, in exchange, she was forced to hand him her house documents. “If you find minerals, the trader will be your only buyer; if you don’t, you’ll either pay back the loan or you will have give him your property,” she explains. “In my case, I found the minerals but I came across a much bigger problem. It was the first time men saw a woman managing a pit and they started spreading a rumour that I was a witch. To save my own life, I had to contract further debts and pay the local chiefs to protect me.” Back then, being accused of witchcraft meant being buried alive. Likewise, working in the mining site proved to be anything but easy. “The biggest challenge for me was working with so many men,” she says. “Until I tied up a strong relationship with some of my workers, many of the diggers would steal from me and I had to pay extra money to find someone who could check on them.” Moreover, further problems arose when men and women started working side by side. “The reason I co-founded ALEFEM was that many women miners after few months fell pregnant,” Intongwa says, grumbling. “Hence, I decided to create a network where I could also tackle their reproductive rights.”

Intongwa’s mining pit is located in the southern part of the Kamituga site, where artisanal mining is flourishing despite the industrial concession, in violation of the mining code. With men engaged in the underground digging and women exhausted from long hours spent dealing with all the remaining tasks, the industrious microcosm that revolves around Intongwa mirrors the complexity of the giant machine, which is Kamituga. At this point, Intongwa is eager to add something.

“There is a difference between the working conditions in my site and the other sites. A very huge difference is that I talk to women and I try to explain to them what rights they have and how they must demand to be treated by men. In the other sites, they don’t do this and women get much more discriminated against.”

“There is a difference between the working conditions in my site and the other sites. A very huge difference is that I talk to women and I try to explain to them what rights they have and how they must demand to be treated by men. In the other sites, they don’t do this and women get much more discriminated against.”

Besides getting her hands dirty, Intongwa is also one of the few female entrepreneurs Kamituga can brag about and she knows that, in order to grow and reach a position of economic solidity, she needs to form a cooperative. “Men don’t want to share with us the revenues they make from mineral sales and they do everything they can to hinder our access to the cooperatives. For this reason, I want to establish a similar organisation for women only,” Intongwa explains. “Sadly, in order to get the authorisation and be able to support this cooperative, we need money, and it’s hard to get the endorsement of women miners who struggle to even make their daily ends meet.” Despite all the difficulties, Intongwa is aware she owes everything to the mining sector. “Even if the men here first accused me of being a witch, I thank God for the opportunities he gave me,” she concludes, as her eyes start filling up with tears.

1

2

3

1 / View of the hills that surround Kamituga village and its nearby mining site.

2 / Footage of people at work in the southern part of Kamituga mining site.

3 / Emilienne Intongwa owns a small mining pit in Kamituga, where women work alongside men.

4 / Emilienne Intongwa holds a small quartz stone, revealing traces of gold, in her hands.

5 / View of the southern non-mechanised part of Kamituga mining site.

4

5

Mama Twangaises

Even if the artisanal mining sector is providing women with new opportunities, it’s still the case today that a great majority of women miners are victim of physical and psychological abuses. In the gold mining site of Kamituga, before walking down the steep slope that leads to the pits, there is a flat area where makeshift metal shacks have been shoved. From there, a repetitive hammering sound comes out non-stop. Inside, sitting shoeless on the ground, there are groups of exhausted women that hit fragments of quartz stones with heavy hammers, using the metal points. The site manager wears big rain boots and, from above, gives orders to the women with deliberate gestures. These women are the mama twangaises, a term that in Congo usually indicates all women miners but, in Kamituga, refers only to the lowest layer of the extraction chain, such as these “stone crushers”. “Forcing women to do this job is the umpteenth form of discrimination,” says Francoise Bulambo, founder of ALEFEM. “As happens in most households, where men stare at women carrying out all domestic tasks, here men don’t want to get their hands dirty and they stand still while women break their backs from the heavy work.” It’s not an euphemism. “Every day I wake up at 6am and I walk two hours to come here,” says 27-year-old Neema Muyengo with sweat dripping down her forehead. She looks at least ten years older than her age. “Every day the only thing I do is crush stones, but I don’t have a choice: I have to look after my family. Many times I don’t even get paid and this job gets useless.” If, after smashing the quartz stone into very fine dust, women find some trace of gold, they earn up to £0.90; if they don’t, they won’t get anything. “Whilst men in the pits always find minerals, even if just in small quantities, we can spend entire days crushing stones for nothing,” confirms Wabisa Masoga, a divorcee with three children. “I must work three times harder than the other women, because as a divorced woman I am constantly exposed to men’s abuses. If I lose a small stone, which perhaps contains gold, men will accuse me of being a thief and will either humiliate or beat me. Sometimes I stole, it’s true, but only out of necessity.” The mama twangaises often have to negotiate their position and access to the sites, offering their bodies as a form of exchange. Even in that case their payment isn’t guaranteed because money always depends on the amount of gold they can find. Making their work more appalling is the toxicity of quartz, whose inhalation – with the passing of time – can cause TB. “Many friends of mine got sick and some died too,” Muyengo says. “If you go to the hospital now, you’ll find many women on their deathbeds due to the quartz dust.”

focus

Who is Marie Rose

Bashwira Nyenyezi?

read

Despite the efforts associations such as ALEFEM make to get the mama twangaises involved in their activities and, therefore, push them to raise their heads up against the abuses they experience every day, only few of them have joined this association so far. “When you earn something, you use the money for your kids and, when you come back the day after, you start everything from scratch,” Masoga says. “Even if we wanted to, we couldn’t save money for other things.” Although the monthly fee for the association is low (approximately £4.50), it’s still too high for women, who struggle to arrive at the end of the day. Like a cat that bites its own tail, if the associations function well, “as long as they are created by women miners themselves,” as researcher Marie Rose Bashwira says, the mama twangaises criticise them because they feel they don’t represent them and won’t ever be able to understand their real problems.

1

2

3

1 / The site manager and his colleagues give orders to the women that pound the stones non-stop.

2 / The twangaises pound the quartz stones with heavy wooden hammers from the metal point.

3 / The twangaises pound the quartz stones with heavy hammers. After that they sieve the powder.

4 / The twangaises pound the quartz stones with heavy wooden hammers from the metal point.

4

5

6

5 / The mining code prevents pregnant women from entering the place where the twangaises work.

6 / The site manager stares at the hardworking mama twangaises from above.

7 / Quartz powder - from which gold is extracted - is highly toxic and, by breathing it, women can get TB.

8 / One of the hardest jobs women only carry out in Kamituga is pounding the quartz stones to get gold.

7

8

Women miners

At the end of both Congolese wars, there was a huge increase in the number of women joining the artisanal (AMS) mining sector. This was due to two main reasons: the economic downturn that spread throughout the eastern provinces, and the decline in the amount of opportunities rural communities were offered by traditional sectors such as agriculture. Women stormed the AMS with relative ease, as doing so didn’t require any particular capital and/or specific skills and education. The truth is that, bearing in mind all the difficulties and problems it still generates, the AMS offered women opportunities they would have never found anywhere else. The main tasks carried out by women in the mining sites can be summed up by the word droumage. Droumage includes different activities, such as crushing, picking and washing minerals, to which the sifting of the minerals reduced to dust, the waste treatment and the sale follow on from. The women that manage the different phases that follow the minerals being dug out of the pit each have a specific name.

The transporteuses (or maman kasomba) carry 25kg sacks of sand or stones from the mining pit, to where either other women (the twangaises) or mining machines grind them. For each run they get paid £1.20. The hydrauliques fetch water to keep the presses cold; the laveuses filter and wash the dust; the bizalu collect the discarded sand; the souteneuses deal with side tasks such as scoring fuel, working tools and food for the miners. Finally, the negociantes deal with the buying and selling of minerals and precious stones. All these activities depend on the daily supply and demand and can vary from day to day. To these women, we must add those responsible for the small restaurants, and the prostitutes. Women miners’ revenues can be as low as £0.45 and, except for traders, seldom go beyond £8 per day.

focus

Tourmaline

read

1

1 / Maria wa Musolella has been collecting, washing and transporting stones for over 20 years. She is tired of her life.

2 / Winine Kalomba is a transporter. For at least five journeys each day she doesn’t earn more than £1.8.

3 / Victorine Mangala is a small trader and has the licence to buy and sell tourmaline in Numbi.

2

3

4

5

6

4 / Wabenga Georgine, 52, has been collecting stones, tossed away by men, since 2004.

5 / Thanks to the mining activity in Rubaya, Dushimana Josee bought her own house and sent her kids to school.

6 / Numbi. Two women rest on stacks of stones which they previously piled up.

7

8

9

7 / Dushimana Josee was an ordinary digger but, with the passing of time, she saved money enough to buy a small mining pit.

8 / Murekatete Beatrice was raised in a family of diggers and was taught that mining is where opportunities lay.

9 / Winine Kalomba is a transporter. She is only 35 years old but she knows she looks much older.

10 / Numbi. At the end of a working day three women check how much coltan they managed to dig.

10

11

12

13

14

15

11 / Numbi. At the end of a working day three women check how much coltan they managed to dig.

12 / Naweza Muligi started as a farmer but today she is an underground digger in Walungu.

13 / Mwamini Makanyaka started as a miner in Nyabibwe and after few years invested her money into trading.

14 / Murekatete is 25 years old and has 4 children. With her work at Numbi mining site, she barely makes ends meet.

15 / Murekatete Beatrice was born in a very poor family but, thanks to the mining sector, she climbed up the economic ladder.

16

17

18

19

16 / “If it was possible to improve our conditions, after so many years I would have become rich but I’m exactly in the same position of when I started.” (Maria wa Musolella)

17 / “My dream was to find a rich man but God didn’t want this for me. He gave me a bad life and now I’m here trying to survive just for my children.” (Murekatete)

18 / Marie-Louise Siuzike is the coordinator of AMOPEMIKAN association, as well as a famous trader in Nyabibwe.

19 / “Women carry a big burden. They are responsible for their families, because men are jobless.” (Wabenga Georgine)

20

21

20 / Forester Nzabuhe Bazibuhe is a big trader of cassiterite, coltan and tourmaline in both Masisi and Kalehe territories.

21 / View of an open pit at Numbi mining site. A woman in red is crushing the stones, looking for coltan.

22 / “I don’t have the trading licence and I sell my minerals to people who set the price and, by reselling them elsewhere, get much higher rates.” (Naweza Muligi)

22

At the end of each working day women miners of Walungu raise up and sing together a chant that tells a lot about their lives, their struggles and their daily achievements.